Display image courtesy of Fresh Water and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington

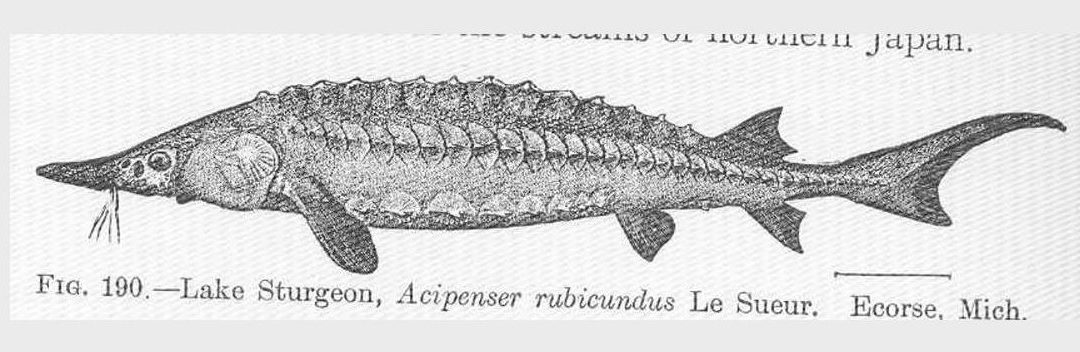

The sturgeon, or Na’me in Anishinaabemowin (the language of the many Great Lakes First Nations communities), is an ancient fish just emerging from danger of extinction in the last century. To look into the history of the Great Lakes sturgeon over the last three hundred years is to journey through the changes in the landscape, with its myriad impacts and unintended consequences, wrought by Euro-American settlement and the market economy that developed with them.

The sturgeon of the Great Lakes is a species whose biology, lifeways and range make it an indicative species of the ecological stresses and changes of our Great Lakes watershed. Nearly all of the historic alterations to Michigan’s lands have made their mark on the water which surrounds us, as well as all of the life within it. Here is a brief survey of some of those changes and their effect on the sturgeon of the Great Lakes.

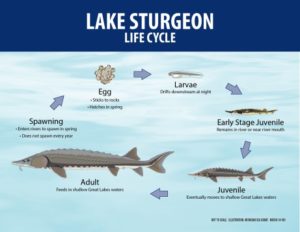

As soon as Michigan’s American settlement began in earnest in the 1820s, the habitats necessary to the sturgeon for reproduction suffered the effects. Perhaps no other activity than the early clearing, draining and plowing of agricultural fields would impact the lakes more. Erosion caused by deforestation silted the gravelly river bottoms where the sturgeon spawned, these silts blocked light, raised temperature and cut off oxygen in the rivers and lakes. Flouring and saw mills grew up in every new settlement; their dams blocking the upstream movement of spawning fish and their mill ponds and races changed the movement and courses of rivers. The sturgeon’s late sexual maturity means that reproduction is especially sensitive to ecological shocks as it ranges for decades in the lakes before returning to spawning ground, undoubtedly altered in the meantime.

Image courtesy of Michigan Sea Grant, University of Michigan

The canals cut across upstate New York would connect different watersheds for the first time, beginning the process of bringing invasive species into the Great Lakes; all of which would change the ecosystem in which the sturgeon had flourished. By the 1840s, rail lines connected Michigan farmers to far away markets and intensified agricultural production, with further deleterious consequences for sturgeon.

Many of the first commercial fishing operations began in the 1830s as re-fitted fur companies. The companies, which declined as taste for peltries changed and the animals were depleted, operated in many of the richest fishing areas of the Lakes. In addition to buying fish from Native villages, many of the earliest commercial fishermen in the Great Lakes were the also Native people, employed as labor in the fishing stations. Mackinac Island witnessed all of these changes as whitefish replaced beaver fur as its most valuable commodity.

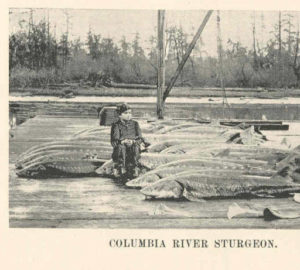

Sturgeons were viewed largely as a nuisance fish during those years, whitefish being the most prized catch. The sturgeon’s huge bulk and bony body tore nets and disrupted the catch of more sought after fish. Sturgeon were killed in their tens of thousands and stacked on the shore to rot or their oily flesh used for fuel in the boilers of ships.

Image courtesy of Fresh Water and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington

The mass deforestation cause by the lumber industry in the, roughly, twenty years from 1870 to 1890 echoed the problems caused by the agricultural clearings earlier, but included additional consequences. The large industrial lumbering mill, unlike their smaller predecessors, were placed at the mouths of rivers for ease of access to transportation on the Lakes. These were dredged and manipulated to power the mills and move the lumber. Massive amounts of detritus from the process clogged the river mouths as the saw dust floated in huge blankets on the surface of the lakes, blocking light and air. Eventually the saw dust would saturate and sink, clogging the gills of fish, including the sturgeon. The first studies of pollution in the Great Lakes were in reaction to vociferous complaints over the logging industry that these early commercial fisherman registered.

As the resources above ground were exhausted, lumbering gave way to mining in northern Michigan as the ports, rail lines and labor used in the timber industry was converted to extract resources underground. This required the dredging of deep channels that could handle the hulls necessary to transport ore through the lakes. Many of these deeper channels were in places retreated to by the sturgeon as their traditional spawning ground up the rivers and streams were blocked or dredged in earlier times. The Detroit River, among the most important spawning grounds for sturgeon in the whole lakes, was heavily dredged in this era period. Spaces necessary for the sturgeon to live and reproduce were increasingly cut off. Mine run-off, chemical byproducts and the disruption of many watersheds by digging and earth moving all contributed their part to the sturgeon’s crisis and decline.

It wasn’t until well after the Civil War in the 1860s that surgeon became a valuable commodity on the lakes. Immigration from central and eastern Europe, where sturgeon and its roe were widely eaten, increased demand. At first, sturgeon was exported from the Great Lakes back to Europe, but soon became a sought after fish in the American market. Industrial use of isinglass, a gelatin-like substance found in fish bladders, in everything from glue to beer was also harvested. Fish oil was extracted and even the bones ground for use.

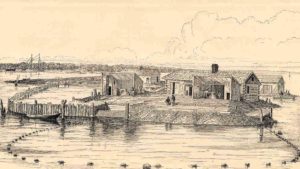

Around Sandusky Bay grew up a major sturgeon fishing station which exploited the rich, shallow waters of western Lake Erie and the mouth of the Detroit River. On Lake St. Claire, Walpole Island and its Native fishers pulled hundreds of tons of the fish, one of the few resources available to them, from the water utilizing new net and hook systems. In the late 1890s sturgeon fishing peaked on the Great Lakes with fishing communities and processing plants lining the shore and nets stretching for, quite literally, miles across the lakes. Grassy Island became the Detroit River’s most important sturgeon fishing station in this period. Within a decade from this peak, the sturgeon would be nearly extinct in the richest fishing grounds and endangered everywhere else.

Grassy Island fishery, 1870s. Image courtesy of Fresh Water and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington

The heavy industry of the early 20th century arrived on the Great Lakes right at the point of the sturgeon’s greatest peril. The huge steel mills and auto plants that brought together the resources of the region in mass production for the first time were the first companies with enough resources to drain the vast wetlands that surrounded much of lower Lake Huron, St. Claire and Lake Erie. Ecosystems like these wetlands had largely survived agriculture and urbanization, but would not survive the massive drainage and shifts in land brought about by industrialization. Entire waterways, like the lower Rouge were encased in concrete and made “dead” in this period as vast amounts of chemicals were dumped in the water. The long lifespan of sturgeons, some can live to be 80 or more years old, has meant that these toxins are gathered and stored in the fish over many decades.

In the 1970s, de-industrialization combined with increased environmental awareness led to a drive to clean up water ways and transform worked over landscapes into recreational and managed natural areas. Renewed interest into the iconic ancient fish of the Great Lakes, the sturgeon, increased and efforts were made to reverse some of the most egregious damage to their habitat. Citizen action led clean ups of watersheds and pushed for the creation of parks and public lands in the former brownfields along the shore. Along with this general push, clubs were organized, like Sturgeon for Tomorrow, determined to reintroduce and protect the species with Native groups increasingly involved in defending their fishing rights and the sturgeon. The Little River Band of Ottawa has an annual release ceremony of sturgeon into the Manistee River.

The scale of the pollution and environmental damage, as well as entrenched commercial and private interests, has made all moves slow and partial. However, great strides have been made in bringing the fish back from the brink of extinction in the lakes. Even Lake St. Clair has seen dramatic rebound in sturgeon population with around 50,000 individuals, the largest group in the Great Lakes, reported in 2015.

While the sturgeon is on the rebound, the Great Lakes ecosystem remains incredibly fragile. Decades of pollution will take centuries to clean, and that is only if new pollution is stopped now. Global warming and climate change will introduce new stressors onto the lakes and require long term planning and integrated solutions. Those solutions will largely come about only if an active citizenry demands them and puts enough pressure on government and private interests to enforce them. We are presented with a huge challenge; the na’me’s environment is our own. As we have seen, the consequences of our actions are often unintended, irreversible and cumulative. If the sturgeon is unable to thrive in the Great lakes, can we? To ensure the long-term viability of the sturgeon is to make possible our own long-term viability on these lakes as well.

Great Lakes Sturgeon Readings

Abel, Kerry M., and Jean Friesen. Aboriginal Resource Use in Canada: Historical and Legal Aspects. Winnipeg, Man.: University of Manitoba Press, 1991.

Ashworth, William. The Late, Great Lakes: An Environmental History. New York: Knopf, 1986.

Nancy Auer, and Dempsey, Dave. The Great Lake Sturgeon. Michigan State University Press, 2013.

Bogue, Margaret Beattie. Fishing the Great Lakes: An Environmental History, 1783-1933. Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin, 2000.

Cohen, Joshua G., Bradford S. Slaughter, Michael A. Kost, and Dennis A. Albert. A Field Guide to the Natural Communities of Michigan, Lansing, Michigan State University, 2014.

Dann, Shari L., and Brandon C. Schroeder. The Life of the Lakes: A Guide to the Great Lakes Fishery. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Sea Grant College Program, 2003.

Doherty, Robert. Disputed Waters: Native Americans and the Great Lakes Fishery. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1990.

Grady, Wayne, Bruce M. Litteljohn, and Emily S. Damstra. The Great Lakes: The Natural History of a Changing Region. Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2007.

Harkness, William John Knox. The lake sturgeon; the history of its fishery and problems of conservation. Toronto: Fish & Wildlife Branch, Ontario Dept. of Lands and Forests, 1961.

Holtgren, Marty. Ogren, Stephanie, and Whyte, Kyle. “Renewing relatives: one tribe’s efforts to bring back an ancient fish”. Earth Island Journal. 30(3):54, Autumn, 2015.

Kerr, S. J. Atlas of Lake Sturgeon Waters in Ontario. Peterborough, Ont.: Ministry, 2002.

Kline, Kathleen Schmitt., Ronald M. Bruch, and Frederick P. Binkowski. People of the Sturgeon: Wisconsin’s Love Affair with an Ancient Fish. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2009.

LeBreton, Greg T. O., and R. Scott. McKinley. Sturgeons and Paddlefish of North America. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 2004.

Little River Band of Ottawa Indians. Manistee Nme: a lake sturgeon success story [videorecording] www.LRBOI.gov, 2012.

Pollock, Michael S. “Review of a species in peril: what we do not know about lake sturgeon may kill them.” Environmental Reviews 23(1):30-43, February 2015.

Riley, John L. The Once and Future Great Lakes Country: An Ecological History, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2013.

Simon, Thomas P., Stewart, Paul M., ed. Coastal Wetlands of the Laurentian Great Lakes: Health, Habitat and Indicators. Bloomington, IN : AuthorHouse, 2006.

Taylor, William W., Abigail J. Lynch, and Nancy J. Leonard. Great Lakes Fisheries Policy & Management: A Binational Perspective. East Lansing: Michigan State UP, 2013.

Winkle, Webster Van. Biology, Management, and Protection of North American Sturgeon. Bethesda, MD: American Fisheries Society, 2002.

Great Lakes Sturgeon Electronic Resources

Goniea, Tom. “The Story of State-licensed Commercial Fishing History on the Great Lakes”. Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Web July 30, 2016.

“Great Lakes Fisheries Heritage Trail”. Michigan SeaGrant. Web July 20, 2016. <http://www.miseagrant.umich.edu/explore/fisheries/great-lakes-fisheries-heritage-trail/>

“Lake Sturgeon”. Michigan SeaGrant. University of Michigan. Web July 30, 2016. <http://www.miseagrant.umich.edu/explore/native-and-invasive-species/species/fish-species-in-michigan-and-the-great-lakes/lake-sturgeon/>

“Little River Band of Ottawa Indians hold sturgeon release”. The Manistee News Advocate, September 14, 2015. Web July 30, 2016. < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EMGtJ420W40.>

“Michigan’s Fisheries 200 Years of Change”. Huron River Watershed Council, 2014. Web July 30, 2016.<http://www.hrwc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Michigan-Fisheries_-200-years.pdf>

“Sturgeon Quiz”. Michigan SeaGrant. University of Michigan. Web July 30, 2016. <http://www.miseagrant.umich.edu/explore/native-and-invasive-species/species/fish-species-in-michigan-and-the-great-lakes/lake-sturgeon/lake-sturgeon-quiz/>

My son has a vague recollection from a class about Lake Erie at Oberlin College that sturgeon slaughter and waste by colonists may have been motivated by strategic warfare against indigenous tribes, akin to the bison slaughter decades later. Can you confirm this for us and/or provide a citation?

Thanks Matt, great work!

I love the images in this post! Excellent work Matt!

I love it to its so interesting.